The story of Australia’s first locally-designed and manufactured tank is a fascinating one. I think that it’s an overlooked part of our history that deserves more recognition than it currently has.

During the Second World War, tanks and other armoured vehicles became increasingly important. Mechanised warfare played out on a much larger scale than any other conflict in history. Although the idea that the Second World War was fought predominantly with mechanised weaponry is a bit of a myth, tanks were produced and used in greater numbers than in any conflict hence or since.

Australia’s decision to build its own tank was very much a product of the time at which it was conceived. By mid-1940, the situation for the Allies was not looking too good. France and the Low Countries had fallen in an incredibly short period of time, Italy was preparing to mount an invasion of Egypt, and Germany seemed poised to launch a naval invasion of the British Isles.

Australia at this time was worried about the prospects of the European Theatre. But importantly, we were also keeping a close eye on developments in the Pacific. While not having yet declared war on the Allies, Japan was becoming increasingly aggressive in the region. This obviously worried Australia as we would be right in their crosshairs should a conflict eventuate.

These developments in Europe and the elimination of most of Britain’s allies meant that very little equipment could be spared for the defence of Australia. Winston Churchill and his government had made this quite clear on several occasions to Prime Minister Robert Menzies and subsequently John Curtin. Defending the Home Isles and the war in Europe were the top priorities.

It was this atmosphere of fear and the lack of available vehicles or equipment that gave rise to the unusual and, I think, misguided decision to design and build our own tank.

This was quite a big leap for a country of only seven million people, limited manufacturing capacity and no experience at all in tank design or fabrication. Design commenced in November 1940. But with little expertise domestically, Australia took inspiration from several existing tanks.

The concept of a ‘Cruiser’ tank, which was the basis for this Australian tank, came from Britain when it was one of the leading countries in tank theory, research and development in the 1920s and 1930s. Basically it moved on from the First World War concept of an ‘infantry tank’ – that is a tank whose primary role was to support slow-moving foot soldiers. Relying on this supporting role for design typically resulted in tanks with thick armour but low speeds.

Cruiser tanks reversed this concept. Much like the transition from battleships to battlecruisers, the new designs sacrificed armour for increased speed, manoeuvrability and agility. This reflected the forefront of armoured theory at the time from such people as B. H . Lidell Hart, John F. C. Fuller and Heinz Guderian. Their overall thesis was that tanks should not be constrained by the speed of infantry, but rather that they should be treated as a fast-paced and potent weapon in their own right. Taking advantage of the attributes of tanks could allow them to completely outflank and outmanoeuvre enemy forces to play havoc with their rear, including lightly-defended but vital supply lines, communications and transport.

The tanks designed from the First World War were totally unfit for these purposes, which is why the Cruiser tank concept came into being.

It was at this group of tanks that the Australian design team began looking. This was probably helped by the fact that Britain sent one of their own experienced tank designers, Colonel Watson, to assist. A French tank expert, Robert Perrier, was also involved in the process for several years. He was later to have quite a significant impact on the choice of engine and suspension, amongst other things that made the Sentinel quite a unique vehicle.

The initial design was modelled against the British Crusader tank (not one of my favourites…) and also included some elements of the new M3 Grant tank from the United States. But although we did take some inspiration from existing tanks, the supply and manufacturing limitiations present in Australia at the time meant that most of the tank was in fact built and designed from scratch by Australians.

By the time the Mark I design was completed in February 1942, in the same month as the most famous and damaging bombing of Darwin, it had changed to include more elements from the US design – probably a good metaphor for a similar change in our foreign policy at the time. This made it less a strictly Cruiser tank, but was still mobile enough to meet the main needs of a modern, independent tank with a top speed of 48 kilometres per hour.

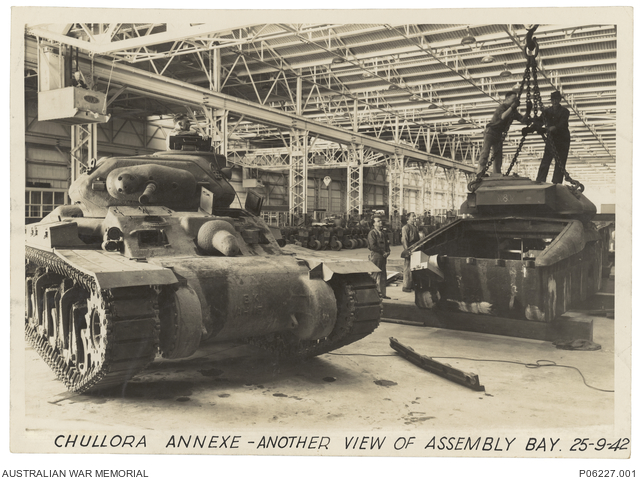

The Sentinel was manufactured in Sydney by the New South Wales Railway Company. It was common during the Second World War for railway factories and infrastructure to be used for military purposes. Industrial capacity that is primarily designed to build locomotives can quite easily be converted into building military vehicles, especially for a country like Australia with limited heavy industry or manufacturing.

I won’t go into many details about its armament, but like most Cruiser tanks it did not pack a sufficient punch. Its 2 pounder gun was quite out of date for a new design by the time production started in 1942. There were some good design elements, such as having a commander separate from other duties (something that several other tank designs lacked for some mystifying reason), reasonably adequate armour and a decent speed.

This tank was also the first in the world to have a completely cast iron hull. The reason for doing this was not for accolades but purely practical. Australia didn’t possess the necessary welded plates that were used on tank models at the time, so this was put forward as a viable alternative.

Overall it could hardly be called into the hall of fame of the greatest tanks of the War. But it wasn’t awful either. Many other countries with vastly more experience and expertise designed and built far worse tanks than the Sentinel. I think we did pretty well, particularly considering the contraints that Australia had to work with at the time.

In the end, no Sentinel tanks were ever used in combat. In fact, their only recorded use outside training and testing was in the 1944 film The Rats of Tobruk. As an aside, it’s quite a good movie and I’d recommend having a look.

There are only a few surviving tanks today out of the 65 that were made. Different sources disagree on the exact number, but it’s somewhere between four and seven. I’m fortunate to have seen two out of the four still publicly accessible – one at the Royal Australian Armoured Corps (RAAC) museum at Puckapunyal and the other at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra. The other survivors appear to be at the Australian Armour and Artillery Museum in Brisbane and the other at the Bovington Tank Museum in the United Kingdom.

Several other marks of the Sentinel tank were designed and some subsequent attempts at building and designing Australian tanks were made, but none were ever built to the same number as the Sentinel. It seems we learned a lot from this first round of tank design and subsequent tanks were significant improvements. We also began programs of modifying British and US tanks that were used by the Australian Army which resulted in some rather interesting and useful variants – such as the Matilda Frog, which was a Matilda tank with a flamethrower replacing the main gun. But after the experiments of designing our own tanks from scratch during the Second World War, Australia never attempted such a feat again.

Some argue that this whole project was a waste of valuable resources, labour and industrial capacity at the time. I agree that in hindsight, this was a poor decision. Even if the Japanese had invaded, a couple of cruiser tanks would not have been much help. It took until June 1943 to make just 65 vehicles – by which time any realistic threat of invasion had disappeared.

The advantages that Australia possessed in resisting a Japanese invasion did not rest on the strength of its armoured corps. The military’s strategy at the time more sensibly relied on our geographical advantages; namely the vast expanse of inhospitable terrain that an invading army would have to cross, the remoteness of population centres from Japanese supply lines and the fact that any invading force would have to travel long distances in vulnerable conditions (i.e. by air or sea, neither of which are easy to pull off even under good circumstances).

Moreover, even if these conditions were somehow overcome, Australian plans to resist called for guerilla warfare in the country, towns and cities. Regular military personnel would quickly train groups of civilians – such as preparing booby traps, laying mines and bushcraft – while the rest of the armed forces would fight delaying tactics (e.g. ambushes) to bog down the Japanese and let nature, disease and starvation take care of the rest.

Anyway, without going into too much more detail on this topic (which I might save for another post), my point is that the sorts of tactics that would have been the most effective against an invading force do not require tanks. In fact, for the sort of fighting that was expected or already expected, medium tanks are a hindrance. A large, heavy and conspicuous vehicle is not generally the sort of thing that you want to take into the jungle with you. Light tanks can have their uses, as the Americans and Japanese found in their island campaigns, but they are not generally necessary to fight effectively in these conditions.

More importantly, as I’ve said several times, Australia did not have large industrial capacity. We were suffering from equipment shortages throughout 1941 – 1943 for things as basic as rifles and uniforms. Allocating large factories to building several dozen tanks that would also need further industrial capacity for maintenance and repair seems to be a strange decision to make in light of this.

Of course, I am aware of the benefits of hindsight and I would not attribute too much blame to those who decided to go ahead with this project. It’s hard to imagine today how isolated Australia felt at the time and how desperate the situation seemed in the dark days of 1941-42. People really felt that Australia was on the edge of a precipice leading to invasion, occupation and subjugation. It’s easy to look back now, over 75 years later, and pass judgement. They should not be pilloried for this decision but I do think that they should have been able to at least understand the strain that building tanks would place on a fledgling manufacturing sector during a time of rationing and shortages.

The Sentinel was a significant feat for Australia, even with all its drawbacks and dubious necessity. For a country with a small population and without any experience in building a tank (and not even that much in operating them), building 65 armoured vehicles of reasonable quality is quite an amazing achievement that is worth remembering and celebrating.

Further reading

- ‘Tank Chats‘ video summary from the Bovington Tank Museum

- Tanks Encyclopedia article

- Wartime films featuring the Sentinel tank from the Australian War Memorial

- Photos featuring the Sentinel tank from the Australian War Memorial

Leave a Reply